Just before heading out south of town to the Bievre Photo Foire I'd read where double Gauss lens designs "draw" better than other designs. I'm not sure what "draw" means, but I'm intrigued and want to find out.

As luck would have it, I picked up a pair of Nikon Nikkor 50mm lenses that implement the classic double Gauss design. So I thought I'd start my investigation by looking at their resolution and compare them to my now standard reference, a Sigma 30mm f/2.8 EX DN E, as well as the beautiful Sony 50mm f/1.8 SEL OSS (APS-C only).

The Nikon lenses in question are Nikkor 50mm f/2 H pre-Ai and Nikkor f/1.8 Ai-S. These are inexpensive and commonly available.

While I had them out I though I'd also see how they behaved when combined with a Zhongyi Lens Turbo II focal reducer adapter.

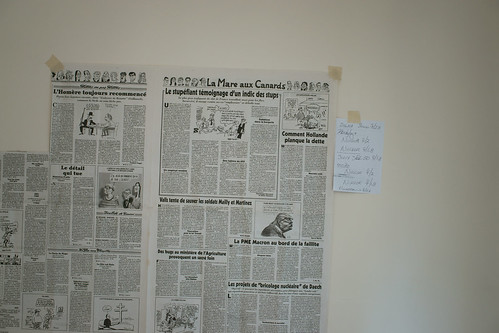

Here is the nice, boring, but richly detailed 2D (ie: flat) comparison setup.

Camera setup -

As luck would have it, I picked up a pair of Nikon Nikkor 50mm lenses that implement the classic double Gauss design. So I thought I'd start my investigation by looking at their resolution and compare them to my now standard reference, a Sigma 30mm f/2.8 EX DN E, as well as the beautiful Sony 50mm f/1.8 SEL OSS (APS-C only).

The Nikon lenses in question are Nikkor 50mm f/2 H pre-Ai and Nikkor f/1.8 Ai-S. These are inexpensive and commonly available.

While I had them out I though I'd also see how they behaved when combined with a Zhongyi Lens Turbo II focal reducer adapter.

Here is the nice, boring, but richly detailed 2D (ie: flat) comparison setup.

Camera setup -

- Some pages out of a recent mailing from a local newspaper taped to the bedroom wall

- Sony A6000 set to "A", 100 ISO, 2second delay

- Massive Manfrotto tripod

- No sharpening applied to the RAW output

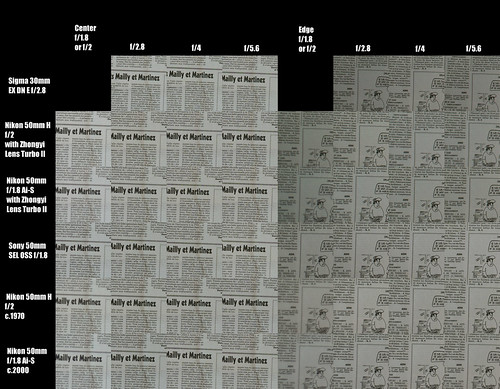

Here are the comparisons. Look at this image at full resolution to note differences between the various elements.

My observations are that the Nikkor 50mm f/1.8 Ai-S is a very fine optic. It's just a touch softer wide open than it's older sister, the 50mm f/2 H pre-Ai. The f/1.8 lens is sharp to the edges, which means it has a very flat field, just like the Sigma 30mm f/2.8 EX DN E.

The Nikkor 50mm f/2 H pre-Ai is very slightly sharper wide open than it's younger sister. The edges never really match the other lenses compared here, but this might be due to field curvature. As we've seen with the copy of the Sony 16mm f/2.8 SEL I've looked at, field curvature can play an important role in how a sharp a scene appears at the edges.

The Sony 50mm f/1.8 SEL OSS (APS-C only) is a very nice optic. I can see why people like this lens. It's sharp from wide open, offers AF and OSS (image stabilization), and while we can't see it here, wonderful out of focus rendition at all apertures.

There you have it: Two inexpensive lenses what perform rather well from wide open, with or without the Zhongyi Lens Turbo II focal reducer.

The Nikkor 50mm f/2 H pre-Ai is very slightly sharper wide open than it's younger sister. The edges never really match the other lenses compared here, but this might be due to field curvature. As we've seen with the copy of the Sony 16mm f/2.8 SEL I've looked at, field curvature can play an important role in how a sharp a scene appears at the edges.

The Sony 50mm f/1.8 SEL OSS (APS-C only) is a very nice optic. I can see why people like this lens. It's sharp from wide open, offers AF and OSS (image stabilization), and while we can't see it here, wonderful out of focus rendition at all apertures.

There you have it: Two inexpensive lenses what perform rather well from wide open, with or without the Zhongyi Lens Turbo II focal reducer.