Last week I spent a wonderful hour and a quarter on the phone with Brooks Jensen, one of the editors of Lenswork Magazine. I was being interviewed for Lenswork Extended #111, wherein my Hauntings of Gothic Ghosts will be published.

I've since thought a bit about our talk and want to take a moment to expand a little on what Brooks and I shared. It seems easier to come back later and think "I could have said that better." So this is my chance to do exactly that.

To begin with, I teasingly blamed M. Jensen for starting me down the path using photographic art as a means of telling a story. His editorials on using portable document format (PDF) to distribute electronic copies of one's work, as well as his thoughts on photography moving in the direction of producing many related images set the tone and direction for my own images. M. Jensen neatly conveyed the potentials in using modern technologies to express one's creativity cleanly and clearly.

He shared something with me that I think is worth repeating. He couldn't remember who said it, but the line goes something like this. In former times, a photographer might be known, after decades of diligent work, for perhaps 12 images. One of which could be called "famous."

Ansel Adam's "Moonrise over Hernandez", Edward Weston's "Pepper number 30", Robert Capa's "Muerte de un miliciano", as well as Steve McCurry's "Afghan Girl" all come to mind.

We then talked about how technology is no longer a barrier to image creation and how this allows current artists to explore a broader range of possibilities. One such possibility is, as I instantly understood it, to create bodies of work. Each collection of work consists of many images. While each image can be individually outstanding, in total they can used to tell moving stories.

I foresee a time when a photographic artist can move beyond being known for a small collection of images to becoming known for a small collection of bodies of work.

Later in our conversation I may not have properly expressed to M. Jensen the strength of influence Lenswork Magazine has had on me. I've read and looked at the magazine for nearly a decade.

Of all the publications, electronic and printed, Lenswork stands out for a number of reasons. They publish photographic _art_, not just a few possibly interesting photos stuck around a large gathering of camera equipment advertisements. Their concentration on photography as art has such a laser beam like quality that one can't help be forget about the technology (cameras, lenses, software, printers, etc.) and think long and hard about what makes a wonderful image. There is no advertising to influence or distract from experiencing fine photography.

I've been known to rile against the on-line forums which do nothing but cater to the adoration and fetish-izing of camera gear. This is why I tend to down-play what cameras and lenses I use. For myself, I've long ago learned these things are probably the least important aspects to image making.

The magazine sent me a collection of works by Kim Kaufman. I was instantly thrilled and my senses were overwhelmed by the beauty of her prints. I understand the technology she used to create these fine images, but this knowledge does nothing to over-power my initial response every time I look at them. In fact, how she made the images means nothing. Certainly not when you realize how drop dead gorgeous her work is.

"Hauntings of Gothic Ghosts" is my second publicized collection of images. My first collection was titled "In the Railyard". It has been published several different ways, including being featured in Lenswork Magazine (Extended #78) as well as in Volume 3 from the Center for Fine Art Photography.

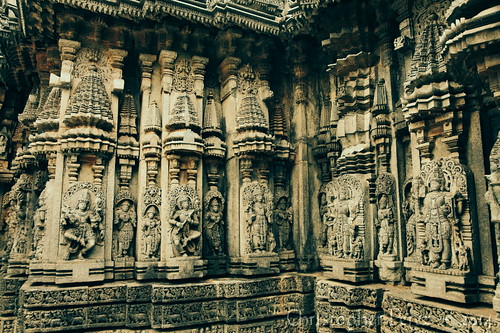

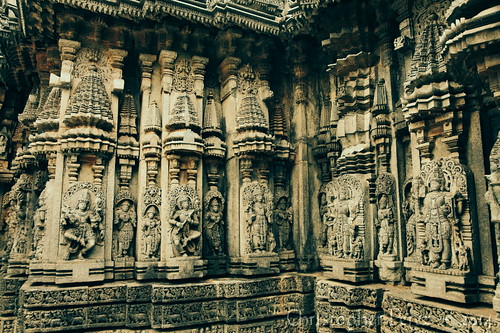

Waiting in the wings are works telling stories about alchemy and it's relation to the Roman Catholic church, further explorations into the nature and power of steam and locomotion, a new work that takes a look at 12th century Hoysala dynasty south Indian spirituality, as well as a body of work related to death and preservation.

After my talk with M. Jensen I feel more strongly compelled than ever that I'm headed "in the right direction." I can't thank him and his crew at Lenswork Magazing enough for helping hone the focus and direction of my own work.

I've since thought a bit about our talk and want to take a moment to expand a little on what Brooks and I shared. It seems easier to come back later and think "I could have said that better." So this is my chance to do exactly that.

To begin with, I teasingly blamed M. Jensen for starting me down the path using photographic art as a means of telling a story. His editorials on using portable document format (PDF) to distribute electronic copies of one's work, as well as his thoughts on photography moving in the direction of producing many related images set the tone and direction for my own images. M. Jensen neatly conveyed the potentials in using modern technologies to express one's creativity cleanly and clearly.

He shared something with me that I think is worth repeating. He couldn't remember who said it, but the line goes something like this. In former times, a photographer might be known, after decades of diligent work, for perhaps 12 images. One of which could be called "famous."

Ansel Adam's "Moonrise over Hernandez", Edward Weston's "Pepper number 30", Robert Capa's "Muerte de un miliciano", as well as Steve McCurry's "Afghan Girl" all come to mind.

We then talked about how technology is no longer a barrier to image creation and how this allows current artists to explore a broader range of possibilities. One such possibility is, as I instantly understood it, to create bodies of work. Each collection of work consists of many images. While each image can be individually outstanding, in total they can used to tell moving stories.

I foresee a time when a photographic artist can move beyond being known for a small collection of images to becoming known for a small collection of bodies of work.

Later in our conversation I may not have properly expressed to M. Jensen the strength of influence Lenswork Magazine has had on me. I've read and looked at the magazine for nearly a decade.

Of all the publications, electronic and printed, Lenswork stands out for a number of reasons. They publish photographic _art_, not just a few possibly interesting photos stuck around a large gathering of camera equipment advertisements. Their concentration on photography as art has such a laser beam like quality that one can't help be forget about the technology (cameras, lenses, software, printers, etc.) and think long and hard about what makes a wonderful image. There is no advertising to influence or distract from experiencing fine photography.

I've been known to rile against the on-line forums which do nothing but cater to the adoration and fetish-izing of camera gear. This is why I tend to down-play what cameras and lenses I use. For myself, I've long ago learned these things are probably the least important aspects to image making.

The magazine sent me a collection of works by Kim Kaufman. I was instantly thrilled and my senses were overwhelmed by the beauty of her prints. I understand the technology she used to create these fine images, but this knowledge does nothing to over-power my initial response every time I look at them. In fact, how she made the images means nothing. Certainly not when you realize how drop dead gorgeous her work is.

"Hauntings of Gothic Ghosts" is my second publicized collection of images. My first collection was titled "In the Railyard". It has been published several different ways, including being featured in Lenswork Magazine (Extended #78) as well as in Volume 3 from the Center for Fine Art Photography.

Waiting in the wings are works telling stories about alchemy and it's relation to the Roman Catholic church, further explorations into the nature and power of steam and locomotion, a new work that takes a look at 12th century Hoysala dynasty south Indian spirituality, as well as a body of work related to death and preservation.

After my talk with M. Jensen I feel more strongly compelled than ever that I'm headed "in the right direction." I can't thank him and his crew at Lenswork Magazing enough for helping hone the focus and direction of my own work.