I was cruising through my Flickr site and stumbled on an image.

It was entered in one of David Hobby's Strobist contests and surprisingly to me it won forth or fifth place.

Did I really do this? Wow.

An exploration of random photographic art related ideas, commentary, and useful information

I was cruising through my Flickr site and stumbled on an image.

It was entered in one of David Hobby's Strobist contests and surprisingly to me it won forth or fifth place.

Did I really do this? Wow.

Here I am, staying for yet another three months in Nice, France. After this year is said and done we'll have been here 6 months. Half a year. Extraordinary year, this.

There's not been much time this trip to consider photography, the craft, the art, the tools, nor the techniques. Yet I snapped a couple images recently that reminded me of something that I've thought about posting.

I wanted to call into question the little matter of lenses and how much importance we place on them.

Sure, most people who make images couldn't work without at least one lens. As we know, and without cutting things too fine, there are plenty of photographers who use pinholes and zone plates.

No. That's not my point. My point is lenses and the minutiae of optical performance and image rendering are largely subjective and up to the image maker.

Outside of ourselves as photographers, who really cares what lens made which image? The viewer? I think not.

Without looking at the EXIF data, here's what I mean. These ancient olive trees are found in the park where they used to play jazz into the wee-hours of the morning during a Nice summer give me pleasure.

I'm happy I had a camera and a lens. I don't think these could be any better to me had I used my "favorite" optics that stayed home back in Paris.

And yet I fret and look and explore and ponder and search and am ready to buy yet another little optic that will somehow make my photographic life "perfect."

I'm a strange being. Really. I am.

It looks like The Online Photographer may be changing the frequency of Mike's posts. Putting food on the table is, of course, the most important thing, right? Sounds like Mike is taking up writing. It'll be interesting to see what he comes up with.

I have followed Mike's blog for years and I've been very happy to have learned as much as I have from reading his posts. His insights into how digital files can be made to look good in black and white are particularly instructional.

Alas, the knowledge of what it takes to convert color into black and white, how to make very large prints from small digital files, how lens designs that influence out of focus rendition, all these things and much much more, when done properly, have been subsumed by and "baked into" the underlying software in current digital systems.

Color grading selection defaults can be set to ensure consistency from image to image. Human perception modeling color to black and white conversion might be the very thing software is based on (and not based on simple color de-saturation). Image stacking for noise reduction, image "up-rez"ing, and resolution improvement now can happen without us even knowing nor caring about what it takes to make the magic happen.

Over on Thom's website, he shared some thoughts on how small the standalone camera photography "ecosystem" has become. The points he makes are, to me, quite valid and relate directly to the "baked into" comment I just made.

Back in film photography days the "ecosystem" was very large. We had the camera and lens makers. We had the film manufacturers. We had photo-labs and camera shops that sold chemistry for film development. We had print paper manufacturers and companies that made enlargers and lenses for enlargers. We had negative and print processor machines we could buy if we could afford them. We had a gallery system and a vast book and magazine publishing engine.

The "ecosystem" was not dominated by a single manufacturer. It couldn't be. The "ecosystem" was simply too large. For all its size and weight, the infrastructure each piece of the system integrated into was complete. Everyone needed everyone else for the whole thing to work.

Today? Things are, quite obviously, different.

Cell phone cameras have become the epicenter of a no-film, no-chemistry, low-overhead, all-electronic "ecosystem." Cameras. Lenses. Network connectivity. Image sharing platforms. Communications. Sharing. Everything is well integrated, even down to having direct connections with the original film-era hold-overs of print making and book and magazine publishing. The number of suppliers that it takes to create this "ecosystem" are substantially fewer than during the film era.

Several short years ago I watched as a tethered camera captured images of a fashion model along the Seine River here in Paris. The images were edited by a small team of people on a laptop computer, color-graded on-site and posted directly to the 'net. All in realtime.

Today I no longer see tethered cameras. Sure, you can take just about any digital stand-alone camera and tether it to a power laptop computer, but why take on that level of overhead when you can do everything from a single device?

Everything can now be shot with a cellphone, by-passing the need for a laptop computer. The team of people is downsized to just one or two people. Everything is transmitted straight across the network to its destination. The distance from idea to final results and distribution can now be incredibly short.

All this leaves me wondering what to do, if anything, with the old, traditional, stand-alone camera/optics systems?

Over a decade ago I mused that wouldn't it be interesting if someone integrated Linux as the base operating system into a camera? Samsung tried this using the Linux derivative, Android, but the project was something of a disaster.

More recently, as in something less than ten years ago, I commented that Sony, the electronics company who should know well how to do this and how to market it, should take the Android OS, throw away the old embedded OS they currently use in their Alpha-series cameras, and create a fully networked, fully integrated, fully connected camera system.

I feel the opportunity is still there for the taking. Except, as Thom notes, there might not be the "vision" of stand alone camera manufacturers to make the logical (to me, at least) leap into the cellphone present.

I'm sure everyone already knows, but "Don't Take Pictures" has shuttered its publication. Perhaps you've read their announcement.

"Dear Readers,

Don’t Take Pictures will cease publication on September 1, 2021. When we launched in the fall of 2013, my Editor’s Letter explained the magazine’s mission as a space to celebrate the thoughtful, creative act of making photographic art. The following year, we launched online to include more timely features about the photographic community. We found that our online and print components needed one another in order to survive.

The world has changed a lot since 2013 and our consumption of print media has evolved as well. In print, our writers and designers spent six months diving deep into the issue’s theme and each artist’s work. Without the distractions of a screen, our readers were encouraged to focus on photography on paper. Online publishing has changed as well. It is time to rethink the purpose of a magazine in the age of social media. For all that is gained by the ability to find photographers with a few clicks of a mouse, much of the grandeur and magic of their artwork is lost when viewed in slideshows, as thumbnails, or as part of an infinite stream of images. The demands of the internet era require a churning of content that is both unfeasible for Don’t Take Pictures’ staff and antithetical to our mission.

The decision to close Don’t Take Pictures was difficult, but its ending should not be mourned—change is not a bad thing. As the art world continues to evolve, our team is constantly rethinking how best to engage with photography in print and digital spaces. We are very proud of our past eight years, 16 beautifully designed print issues, and hundreds of online articles that exemplified what Don’t Take Pictures is about—great photography and great writing. We would like to extended a special thanks to the 90 artists we were honored to feature in print.

Readers whose print subscriptions included an issue this September have been refunded. The Don’t Take Pictures website will remain online as an archive and resource for the foreseeable future, with all previous issues available as PDFs. It has been an absolute honor to share the work of emerging photographers and arts writers in print and online for the past eight years. We appreciate everyone who read our articles online, engaged with us on social media, or read Don’t Take Pictures in print.

Sincerely,

Kat Kiernan, Editor-in-Chief"

I feel at the bottom of all this is an important point. The purpose of a photograph has changed dramatically in recent time. How we consume images, how we look at them, why we look at them, and what they mean to us has little relation to how we engaged images just a decade ago.

This is why I've scaled back my online presence. I now have just this blog and my Flickr page. That's it. Nothing more.

Us older folk who tend to "remember when" are dying off. Photography had its day in the sun. Now the experience of image making is, for me, reduced to sharing what I still find interesting and pleasurable. I do this regardless of if there is an audience or a group of photographers I can share with, or not.

Someday I may feel differently, but for now, that is how it is.

Super Resolution, where you take a small image and increase its spacial dimensions and try to retain as much detail as possible, has been an interesting topic for photographers over the years.

Google recently published something related to two different approaches.

They used an artificial intelligence to learn and then apply results.

"...diffusion models, originally proposed in 2015, have seen a recent revival in interest due to their training stability and their promising sample quality results on image and audio generation. Thus, they offer potentially favorable trade-offs compared to other types of deep generative models. Diffusion models work by corrupting the training data by progressively adding Gaussian noise, slowly wiping out details in the data until it becomes pure noise, and then training a neural network to reverse this corruption process. Running this reversed corruption process synthesizes data from pure noise by gradually denoising it until a clean sample is produced. This synthesis procedure can be interpreted as an optimization algorithm that follows the gradient of the data density to produce likely samples..."

I wonder how well it might work for amateur and professional photographers? Perhaps we'll get a chance to see some day.

The older the I get the more important the size and weight of camera gear has become.

In fact, there was a time about seven years ago when I started doing push ups to build up my arms. The Canon 5D MkII and 7D cameras owned then, along with two or three L-glass lenses were becoming too much for me to carry for a long time. I would come back from a la traversee de Paris event exhausted.

One of the conversations folks were having online at the time was how nice it would be to have a full frame digital camera that had dimensions and weight similar to the old Canon AE-1. If I remember correctly, Canon was saying they considered that to be the "perfect" camera size. I can't recall their reasoning, but looking at the 1D and 1Ds I wondered why they felt they had to make those cameras so huge.

Not too long after I bought a new Sony A6000. At first I didn't use it much as I thought the full frame Canon 5D _must_ have better image quality than the smaller APS-C A6000. I caught on to the truth soon enough. Sony sensors were and are nothing short of brilliant and I soon sold all my Canon gear.

I'm not sure why I thought about this recently. Perhaps it has to do with the sizes of the Nikon and Canon mirrorless offerings. They're still quite large and I wondered why that could be?

In any event, I thought I'd put down sizes and weights just to compare various cameras, new and old. So, starting with the shortest base-length camera body and ending with the longest -

*Sony NEX-5T - 111mm x 59mm x 39mm - 329grams with 16mm f/2.8 pancake lens

*Sony NEX-5T - 111mm x 59mm x 39mm - 392grams with 16-50mm kit lens

*Sony NEX-5T - 111mm x 59mm x 39mm - 421grams with 30mm Sigma EX DN lens

*Sony A6000 - 120mm x 67mm x 45mm - 468grams with kit lens

*Sony A7 - 127mm x 94mm x 48mm - 769grams with kit lens

Nikon Z7 - 134mm x 101mm x 68mm - 1175grams with kit lens

Leica M4 - 138mm x 77mm x 38mm - 550grams body only

Canon R5 - 138mm x 97mm x 88mm - 738grams body, battery, CF card

Canon AE-1 - 141mm x 87mm x 47mm - 590grams body only

*Sony cameras were weighed with batteries and memory cards.

A quick glance at the list re-confirms for me that Sony continues to meet my lightest/smallest camera goals.

Here is how I setup the back button focus on a Sony NEX7.

Menu -> Setup -> Custom Key Settings -> AF/MF Control

Menu -> Camera -> AF/MF Select -> Manual Focus

Menu -> Setup -> AF/MF Control -> Hold

Menu -> Setup -> Function Settings -> Function Settings 1 -> Focus Settings (though I really don't use this one at all)

I like using this setup for nearly all situations when using this NEX. The only problem with the Sony NEX-7 AF system is that it is slow compared with the Sony A6000. If memory serves, the 7's AF system is contrast detect and not phase lock.

For this reason I tend assign the heavy lifting for motorsports activities to the A6000. I quite happily use, on the other hand, the NEX-7 in low stress, slow change situations, such as travel.

I see that I need to document for future reference how I set my Sony A6000 to back button focus. I have reached the age where I forget things.

The whole "back button focus" interest started when I found the camera would select something of stronger contrast in the background to focus on when the subject was smooth and of lower overall contrast.

For example, when I photograph cars they tend to be smooth, broad areas that the AF system might have trouble locking onto when something in the background is so much easier for it to acquire.

Diving into the menu system...

Then I set the AF system to the smallest center point. The "wide" and "center" selections are too broad and things in the background might be selected instead of the precise thing I want. Hence the selection of an AF "point".

When I want to focus, I press the AEL button on the back of the camera. There is no AF when I press the shutter release.

The usage steps are -I like this approach when using AF lenses. It is a way of emulating the point of focus of a manual lens without the hassle of toggling the magnifier, focusing, then turning the magnifier off before re-composition.

Once I got into the habit of using back button focus on certain subjects, I found it was easiest for me to simply use this approach for nearly everything. It makes me think a moment or two about what I want in best focus before hitting the shutter release.

Readers likely by now know how much of a nut I am about optics and minutia and details and things that really don't seem to matter to normal people.

Certainly I've learned a lot over the years by poking and prodding at the subject, including that well designed optics are a result of balancing trade-offs. However, explanations of these trade-offs are all too often are missing from the marketing literature. It seems as if there is a distinct disconnect between engineering and marketing.

Helpful descriptions like what makes a good portrait lens are very rare. In fact, I only know of one document that a manufacturer produced that guided users. That was with the specialized Kodak Portrait lenses.

More normally interested parties are left to sort things out for themselves.

A good example of this is Nikon's famous 105mm f/2.5 Nikkor-P. It was commonly accepted that it is a wonderful optic, but no one could tell you _why_. The marketing literature of the day is woefully lacking in explaining the unique property of that lens.

It is only relatively recently with Nikon's 1000 and 1 Nights lens history series that we learn the designers controlled the under-corrected spherical aberrations behind the point of focus. Here is how Nikon now explains it.

"... The lens also has characteristics of spherical aberration and coma. Basically close-range aberration variation is small, but at portrait distances the correction for aberration seems to be slightly insufficient. The insufficiency as far as spherical aberration in particular is what makes defocus background appeared beautiful. The aberration balance has been calculated carefully for use in portraits. When the aperture is open contrast is good, and delineation is soft..."

That, right there, is why that 105mm lens is so gorgeous.

Being left to sort things out for myself, with years, experience, and patience, I think I've hit upon the things that make a lens interesting to me. Resolution is a given. As it turns out that is probably the easiest quality to design into a lens. Even sub-$100 kit lenses are "sharp."

Field flatness is not all that important to me, unless, as in the case of the Nikon Nikkor 35-105mm f/3.5-4.5 zoom, the field curvature is extreme. There is also the case of the Zhongyi LensTurbo II focal reducer with, with certain lenses, such as the Nikon Nikkor 24mm f/2.8 Ai, introduces an obvious amount of curvature to the field. Other than that, field curvature is just one of those things to think about in specialized applications, such a document photography where a flat field might be helpful.

Other lens "faults" such as chromatic aberration can now be corrected in image processing software.

Which leaves me with the aforementioned spherical aberration. When a designer deliberately uses this form of aberration in a lens, it can help lead to "creamy" smooth out of focus rendition. This, I've come to learn, is what Nikon carefully considered in their manual focus lens designs. I'm thinking of the fabulous 85mm f/1.8 H/H.C./K and famous 105mm f/2.5 P lenses, as well as, perhaps surprisingly, Nikon's 75-150mm f/3.5 and Nikkor 100-300mm f/5.6 AiS optics.

As I said, it can take time to sort out which properties might matter to you. This is why I'm pretty sure why Leica once advised that photographers use a lens for a year before deciding if they liked it or not.

Et voila! this is how I settled on Nikon lenses. I've been using them consistently for many years after having used Canon lenses for even longer.

The Zeiss has a very very small mark on the front glass. It's really difficult to see the defect and it might only be a rub on the coating as the glass looks to be OK. The lens has proved to be a good choice, being well constructed and pleasingly sharp and all that.

However, I hadn't taken it as "seriously" as I do the Nikkors. The new to me Zeiss lens remained "just another lens."

In fact, just the other day I enthused over a beat-up Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/4 Ai and its out of focus rendition. So many project possibilities came to mind and I was excited to haul this thing into the wild to make a few images with it.An opportunity to photograph a music group plopped into my lap and I wanted to confirm which lens(es) I would use. Wanting the most flexible solution for this studio photoshoot I thought perhaps I should use the 16-70mm ZA. And I'd better check things out beforehand. As "beautiful out of focus" references I used my 85mm and 105mm Nikkors to compare them with the new to me Zeiss ZA.

I didn't expect much out of the Zeiss for out of focus rendition. I'd read, for instance, that Zeiss' 24-70mm f/4 lens for full frame Sony cameras had "busy" out of focus rendition. Could the little ZA lens really be any different?

... er... yes... I was in for a little surprise... and I like good surprises... so yipee!!! Looking at the results at 70mm f/4 with the smaller APS-C 16-70mm Zeiss forced me to evolve my thoughts on the subject.

Take a look at the following images, and as always, click on and enlarge them to 100percent. Pay particular attention to the lettering/numbering around the inside front ring as well as the out of focus qualities of the rear cap.

Nikon Nikkor (Xenotar version) 105mm f/2.5

photographed with

Sony A6000 - ISO100

Zeiss 16-70mm f/4 ZA OSS

The differences are rather subtle between the images. Yet to my eyes the Zeiss is "smoother" in the out of focus regions than the Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/4. The "edges" rendered with the ZA lens are "rounder."

Don't get me wrong. The Micro-Nikkor is quite wonderful and I'm certainly not in any hurry to kick it to the curb. It's just that the Zeiss does something that I find "special."

It turns out the 16-70mm f/4 ZA OSS is actually a very nice lens. Whoever designed it really put effort into it to get so many details "right."

What a find, eh?

In a prior article I took a look at copying 4x5inch black and white negatives using a 24megapixel full-frame digital camera and an old film-era macro lens.

It left me to ponder the question of how much more "resolution" could be gotten by moving the lens closer to a negative and stitching several image sections together. It could be interesting to find the point where the digital system would start recording film grain and give no further "resolution" increase by moving even closer.

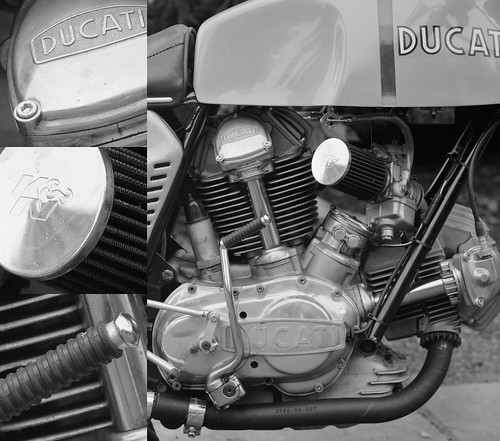

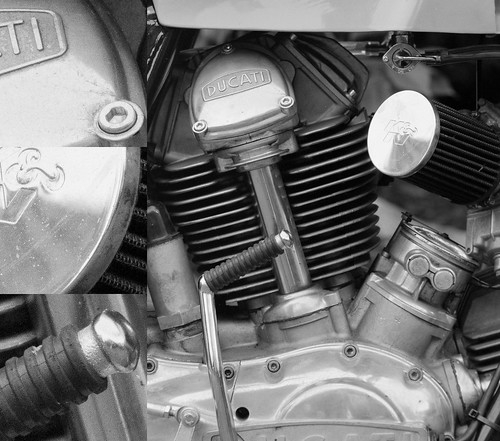

The subject is a lovely 1975 Ducati 750GT. I bought this from a friend who had made it into a quasi-"750 Sport." It was a gorgeous bike and I loved riding that Duc. One year I rode it to the Steamboat Springs motorcycle racing event from Oregon. She delivered 55miles per gallon a 75 miles per hour. Talk about efficiency!

This version of the 750cc 90 degree V-twin came with spring actuated valves, not the more legendary desomodromic valve train that Ducati is rightfully famous for. Still, the motor was sufficiently powerful, easy to control, and had nothing to rate against it as far as I was concerned.

Fabio Taglioni had designed or specified nearly everything about these bevel-drive bikes. The layout, engineering, and manufacturing were outstanding. My bike worked like a beautifully made watch. There was a finesse that seemed missing from all other motorcycles i ever rode (and I've ridden just about every road bike ever made from 1973 through to the late-1980's).

I owned another interesting spring valve Ducati. It was a 1977 860GT. Few people liked the bike and I can remember seeing new, unsold examples sitting of showroom floors well into the 1980's.

Never sure why people didn't like it, I found it had "grunt" on the road. It felt like a person could pull tree stumps out of the ground with one. I rode mine for years without experiencing any problems. It, too, had a finesse that was undeniable.

Even if I find such details interesting, these have nothing to do with photography. So back to is, shall we?

The following image is a single photograph taken of the entire negative using an early model Sony A7 24mpixel camera and an ancient Nikon Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/3.5 lens.

[As always, click on the images and then enlarge them to 100percent]

Entire negative in one shot -

Scene on the right

100percent enlarged sections on the left

The following image is a single photograph that represents approximately 50 percent of the area of the entire negative.

50percent negative -

Scene on the right

100percent enlarged sections on the left

Lastly, the following image is a single photograph that represents approximately 25 percent of the are of the entire negative.

25percent negative -

Scene on the right

100percent enlarged sections on the left

As you can see, film grain is just becoming visible in the 50 percent enlargement. A stitched image of this magnification would be approximately 10,000 pixels across on the long dimension from a 4x5inch negative. Image details look pretty good to my eyes.

From the last image we can see that film grain is clearly visible in the 25 percent area enlargement. I'm not sure how useful it would be to make an image 15,000 or 20,000 pixels across on the long dimension with this grain size, but, as you can see, such a thing would be easily possible.

If I were to make prints larger than 20x24inches, perhaps I would "feel better" about photographing a negative in sections, and then stitching them into a rather large file.

I'm not sure how this would look in practice as I no longer have a printer and no place to store prints. On the other hand, for sharing some of my old work, I think a single full negative digital image should work just fine.

Even as we are opening up over here after 18+ months of a pandemic I find I still have a bit of time on my hands.

I also have a medium sized box filled with black and white film negatives that I brought back with me the last time we were State-side. What better thing to do than to see if my work has at all progressed over the decades?

To find out what I wanted to find out I needed to make digital "scans" of a few negatives. I was concerned that 24mpixels would be "enough" resolution to make a "one shot" copying effort worthwhile. It's all I have on hand at the moment as the higher megapixel cameras are well out of my financial reach.

My fear was that I might need to photograph each negative in sections, then stitch them together into a larger file to get the kind of "resolution" I felt large black and white negatives were capable of.

Here is the "copy stand" setup I used -

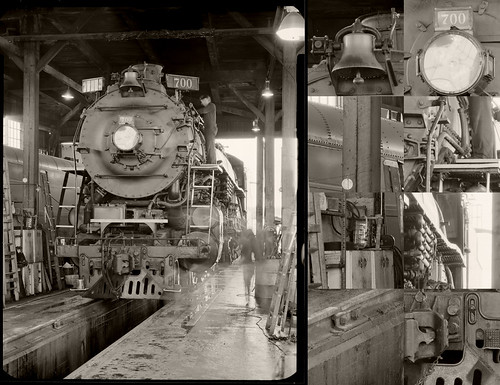

The first train image is of SP4449, a 1941 Lima manufactured streamlined 4-8-4 Northern class steam locomotive. She was the locomotive that pulled the "Freedom Train" around the USA in 1976.

The film is Polaroid Type55 Positive/Negative. I wish someone could reliably reproduce this film. If they could I'd be sorely tempted to buy another 4x5 camera and a lens or two. This was wonderful material to work with.

As you no doubt are already aware, this film gave a print and a negative at the same time. I loved working with this material. To get decent density in the negative I usually shot it at ISO32 or ISO25. This would leave the print slightly over-exposed, but this didn't matter to me as what I was really after was the neg.

I lived for 18 years in Hillsboro, Oregon. Occasionally the city of Portland's big steam locomotives could be heard on the tracks that ran to the south of the house. Often I'd grab a camera and jump into the car to head over to see what I could see.

Coming to the subject of deciding if 24mpixel is enough "resolution" to capture something decent off an old 4x5inch negative in a single shot, here is a photo of SP4449 at rest during one of its Hillsboro runs.

SP4449 ~ Hillsboro

Schneider 110mm XL f/5.6

Full Scene on top

100percent crop sections across the bottom

To my eyes things don't look too bad. In fact, this looks entirely usable. Just to confirm this I would like to look at a second image.

The city of Portland owns another steam locomotive. SPS700 is an "E1" 4-8-4 Northern class steam locomotive that was built by Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1938. She is physically larger than her SP4449 sister.

After I started chasing these around Hillsboro I made a concerted effort to find the roundhouse that I heard they lived in. It wasn't exactly easy and one had to be careful about visiting. At that time the roundhouse was on heavily rail-trafficed BNSF property and the steam locomotive crews were only on site at the roundhouse on certain days of the week.

Once I sorted all this out, I found the roundhouse to be a magical place. There were actually three steam locomotives housed there, along with several early diesel electric locomotives, passenger cars, with various parts and pieces laying all around.

SPS700 ~ Roundhouse

Schneider 110mm XL f/5.6

Full Scene on the left

100percent crop sections down the right

I have to say that, yes, this "works." And, yes, those are backlit/sidelit raindrops you see hanging off the bell. The resolution is, again to my eyes, outstanding. The dynamic range of that old Polaroid film is truly outstanding, too.

What I have on hand is a small fraction of the film I had up until a few years ago when I whittled everything down to just what I could carry back to Europe with me. I tried to keep the most interesting images. A lot has been left behind in a landfill somewhere. Fortunately I still retain a satisfying number of negatives.

A larger project, or series of projects, now appears on the horizon. I'm really enjoying working with these old train photos.

I recently purchased a new studio strobe and remote trigger and had trouble getting the system set up to communicate between the trigger and the strobe.

This article documents a setup that seems to work for me. At least for now.

The strobe is a Godox MS300. The instructions on its use are found here.

The trigger is a Godox XT16. The instructions on its use are found here.

Looking at the back of the trigger I saw a dial that goes from 0-F and is labeled POWER. Hmmm. What does _that_ mean?

I found a video on YouTube, but my Hindi isn't up to scratch. I turned the sound off and tried to follow along with the button pressings. I kind of got the hang of it, but I watched a second video that proved to be a little more helpful, even though the remote trigger was not the model I have.

Shown here are

the Godox XT16 remote controller

mounted on a Sony NEX-5T and

MS300 strobe side by side

so I can see both display

and button systems

In short, here is what I found -

On the MS300 strobe -

On the XT16 remote trigger -

There are two things that remain a mystery to me.

On the XT16 remote trigger there is a button labeled SET. Pressing it for 2 seconds changes the display. Pressing it again for 2 seconds changes to something different on the display.

It appears there are three modes or styles for displaying the light output of the MS300 strobe, if indeed these are what the three different numbering systems refer to. One display style representation is a fraction of the overall light output (ie: 1/32 +0.3EV). Another style starts with the number 1 and the other starts with the number 5.

I can't find a clear indication of how these three XT16 display labeling styles correspond to the MS300.

A second thing that confuses me is that there doesn't seem to be any way of controlling the light output display value on the strobe. I have seen the MS300 display two different light output styles - the fractional light output and the display style numbering system that starts with "5."

Worst still, the MS300 light output display style changes randomly. Even worse than that, these display styles appear to be independent of what is displayed on the XT16 remote trigger.

I expected that once I'd selected the display style on the XT16 that these would be communicated to the MS300, but they are not. Or, minimally, I thought I would be able to select the light-output display style on the MS300, but I can't find the magic incantation.

Nowhere is there any description of how these things should or could inter-relate. There is no indication of their meaning, other than what is clearly implied by the fractional light-output style of display.

[rant on] The inconsistencies in these products bother me. From an engineering, marketing, and product integration perspective the Chinese could have done a far better job. This isn't complex stuff, really.

They are very good at ripping off western product implementations, but the Chinese still have seemingly zero understanding of the importance to also rip off western designers sense of what it takes to build a system of well integrated products. Based on my initial experience, usability and labeling is a mess chez Godox.

Further, there isn't enough "tribal knowledge" that comes with use that can help guide newbies to this kind of product set such as myself. So I'm left thrashing things out as best I can.

In the end, I feel I got exactly what I paid for. I have an adjustable light output remote controllable strobe with rather little to guide me as to how the system actually works nor what parts of the display system are trying to communicate. [rant off]

I had this lens up for sale not too long ago. No one seemed to want to bite, even though I'd put a rather low price on it. So I took down the forsale ad on my Nikon Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/4 Ai lens, put it into its case, and put it back on the shelf.

My wife and I then went on winter holiday, where, for the second year in a row, we got stuck in Nice.

OK. Just how "stuck" can one actually be when in Nice?

Well, we were "locked down" by the French government due to the extreme pandemic conditions in the Alps Maritime (where Nice is located). All social events, art exhibitions, and concerts were cancelled and banned until further notice. Travel was limited to 10km from your place of residence. We couldn't legally return to Paris, even if we wanted to.

Of course, there was the beautiful Mediterranean sun and warm winter weather, right? Er. No. Not this year. It rained. And it rained. And it rained some more. And it was cold. There was snow in the hills around Nice well into April. Nothing was open, though we could get "take-out" from a couple restaurants in the area, including a wonderful "hole in the wall" pizza place.

I know. I'm bitching and moaning about being "locked down" in paradise.

It did give me time to think, though. One of the things I thought about were my manual focus Nikkor lenses. I still have too many of them for one man's own good. I enjoy having them. I enjoy photographing with them.

When we were finally able to reach Paris again I was delighted to see all my "stuff" and "things." Just seeing my several boxes of toys made me smile.

I'd taken a look at out of focus rendition in an earlier article. There wasn't much to say except the Nikon Micro-Nikkor 105mm f/4 Ai didn't look a whole lot different than some of my other lenses. Resolution is as good as anything else. It was nice but unremarkable. I hadn't found must "magic" in the lens.

After photographing three lenses for other articles found here, I

turned the Sony A7 and Nikon Micro-Nikkor f/4 Ai on a pretty little orchid my

wife brought home. When looking at the images I thought "gosh, now

don't those look nice?" The out of focus rendition behind the point of

focus was quite unexpectedly smooth and delicate.

My thoughts on this old "Heliar" design Micro-Nikkor lens needed an evolution in light (ahem!) of those orchid photos. Then I looked more carefully at the lens portraits I'd taken earlier the same day and thought "well well well then, aren't those just drop dead gorgeous?"

Maybe I'd been a little too hasty in putting this old beat-up lens up forsale?

Next month there will be a couple car gatherings. One in particular should be an interesting event to try this ugly duckling of a Nikon Micro-Nikkor f/4 Ai. Hopefully my current more highly evolved thoughts will be soon proven correct.

Yes. I know. Like everyone else I've been coupe'd up far too long. I find myself _wanting_ to love this lens and it gives me pleasure to think I've found where the "magic" lay.

In 2016 my wife and I visited le Grand Train, a short-term food court event held in an old SNCF railyard on the north side of Paris.

After my usual whinging and thrashing over what to carry by way of camera I finally settled on one of my Sony NEX-5T, a straight-through adapter, and the Nikon Nikkor 35mm f/2 Ai I had at the time. On the crop-sensor NEX the full frame equivalent works out to around 52mm's, or what we used to call a "standard" focal length.

Soon after, I sold that lens. Of course, me being me, I soon regretted the sale. I'd gotten around 150 bux out of it to help finance the purchase of something else I thought I desperately "needed." My aging brain can't remember what I bought, but I can still remember that lens.

On the rendition of the images I took that day... I don't know... there is just "something" about them that appeals to me, even now. Some of it is the Capture One "gold" somethingorother preset I had access to at the time. Some of it, I felt, had to be the way the lens renders when shot wide open.

Here are two color image examples from le Grand Train.

Artful Headlight

le Grand Train

Nikkor 35mm f/2 Ai

Business End

le Grand Train

Nikkor 35mm f/2 Ai

The lens wasn't "clinically sharp" at f/2, but compared with modern lenses it could certainly "hold it's own." If I needed "clinically sharp", I could certainly get things to look like anything else in the lens kit with a little "smart sharpen" or "capture sharpen" during processing.

As a side note, I believe Lightroom and RawTherapee have similar "capture sharpen" functions. This can be applied to a file as a way to offset anti-aliasing sensor filters as well as to offset lens "softness."

A couple years later I was browsing That Auction Site out of boredom. I came across an early Nikkor-O pre-Ai copy. Patiently I waited for the auction timer to count down. Patiently I watched as no one bid. Patiently I hoped I could win. Patience does not come easy to me. I did the best I could. Trying to be virtuous and all that... et... voila! I sniped it for less than 50 bux, delivered. When it arrived it was in even better condition than I'd thought from looking at the auction photos. Happiness ensued.

This "Second Chance" Nikkor-O, like its Ai series successor, renders beautifully. Wide open this single coated lens exhibits just a hint of "sparkle" in the highlights that the multi-coated Ai version I had did not. The out of focus rendition behind the point of focus is Nikon's typical gorgeous smooth under-corrected spherical aberration yumminess that sends me over the moon in delight.

These days the "Second Chance" 35mm f/2 practically lives on a pretty, very low shutter count Sony A7 that I'd also picked up for cheap.

With the re-opening after a long, difficult pandemic, I'm hopeful there will be plenty of future opportunities to use the combo A7/Nikkor-O. It'd be fun to come away with a few more good images.

In an earlier post I said "... Not that I needed a third 105mm lens or anything like that, but, apparently I needed a third 105mm lens... It appears that I'm the second owner of a gorgeous version of an updated dual rear element optic..."

The development history of the fabled Nikkor-P 105mm f/2.5 lens is well known.

I remember reading somewhere that Nikon took their c.1954 10,5cm rangefinder lens, shaved 1mm off the rear element to clear the Nikon F SLR mirror, and introduced that lens in 1966.

Nikon's own Thousand and One Nights series documents some of this from a designer perspective. They say...

"...Compared to the previous model with the [Nikkor-P early SLR] Sonnar type lens construction, [the updated Nikkor-P Xenotar type] offers significant improvements in close-range aberration fluctuation, as well as peripheral light, spherical aberration and coma. In particular, it delivers a beautiful balance of focused and defocused (blurred) images, as well as higher resolution with natural gradation. The Xenotar-type lens design with the ideal aberration correction made it the perfect lens for portraits..."

I once again have one of each version of this optic. The chrome-nose 105mm on the right in the top image is the earlier 105mm SLR single rear element Sonnar design. The black-nose 105mm lens on the left is the 1970 Xenotar update version.

Of course I couldn't help myself and I had to see if I could see these things. Additionally, I wanted to see how the two lens designs handle highlight transitions. So I selected a scene that included white screen door material and an edge of a sliding glass door. I also "Capture Sharpened" images from both lenses to see how much the software normalizes output resolution. Lastly, I wanted to confirm that in terms of "sharpness" that even 50 year old lenses can still "look good", even by today's hyper-sharp standards.

[click on the following image and enlarge to 100 percent]

Now that you've had a good squint at the output, can you tell any difference between the two? I can't. Well, maybe a little. If I really squint hard, stand on the tippy-toes of my left leg, spin counter-clockwise, and chant "lenses lenses lenses." Any minor differences are really difficult to see and might quickly be put down to focusing differences, if any.

So what have I proven? Well, both lens designs seem to render highlights very similarly. Both can be made to appear very sharp. Both handle shadow details equally well, even though they are single coated. And I can re-affirm that I like both of these lens versions equally.

This leaves me in something of a conundrum. Which lens would I carry and why?

I recently downsized my selection of manual focus lenses from an unmanageable to a nearly manageable number of items.

To celebrate, I thought I'd do yet another "family portrait."

Missing from the portrait are two lenses. One that for some reason didn't make it to the table. That would be the rather too shy for its own good Nikon Nikkor 50mm f/2 Ai. It should've gone right next to the pretty little 50mm f/1.8 AiS "pancake" lens at right in the front row.

The second is a lens that arrived a couple days after I took the above photograph. Not that I needed a third 105mm lens or anything like that, but, apparently I needed a third 105mm lens. It would've slotted in next to the gorgeous 35mm f/2 on the right and just in front of the early design single rear element Nikkor-P 105mm that is also on the right.

It appears that I'm the second owner of a gorgeous version of an updated dual rear element optic. It is pre-Ai and, according to the documentation I received, was purchased in late 1973 from a shop here in Paris, France. There are only a few indications on the focusing ring that the lens is not new.

Along with the lens came two marketing brochures. They describe Nikkor lenses from the late pre-Ai period as well as from the early Ai time frame.

Here is the scanned pre-Ai lens document.

Here is the scanned early Ai lens document.

When I was young I poured through these two catalogues of lenses. My imagination was thoroughly fired up by what I saw. Since I now have these on hand I decided to scan them. For posterity sake and all that.

You may have noticed that 135mm lenses are missing from the family portrait. I'll have to wait to see how much longer that remains the case. I miss the 135mm Ai f/3.5. I'd sold it in a fit of downsizing. I think I went too far.

If I'm not careful and before I know it I'm certain to again reach a clearly unmanageable number of manual focus lenses.

My only justification is that I'm trying my darnedest to limit the budget to well under 50Euro each. That, and the fact I'm very happy with having found an early Sony A7 24mpixel full frame camera that arrived with less than 800 clicks on the shutter. It "needs" lenses, right?

Well, that was quick.

I'm back with yet another article on resolution and such Madness. This time I compare photographs taken using a Sony HX90V 18mpixel 30x zoom point and shoot against a Motorola G8 Power that I recently picked up on sale.

The setup was a street scene. The camera and phone were shot handheld. I selected the focal lengths closest to 24mm full frame equivalent. On the Moto G8P this meant selecting the middle/default lens, where I set the resolution to 16mpixel. I let the devices deliver the output jpgs using their default image processing modes.

That's it. Easy peasy.

Here is a comparison of images between the two devices.

As is quickly confirmed, the Motorola fixed focal length lens system outperforms the Sony point and shoot at this focal length. Images out of the Moto G8P are sharp to the very edges. The Moto G8P colors are more pleasing to my eyes where the Sony color tones feel slightly "washed out."

Compared to APS-C or Full Frame images, these devices produce somewhat "water colory" rendition. Yet, when downsized for viewing across the web images from the small devices aren't half bad.

Of course the Moto G8P doesn't have the kind of reach that the 30x zoom Sony HX90V has. But after spending far too long cooling our Covid 19 pandemic jets in Nice, France this past winter where I used the Sony quite often, I realized yet again that I seldom use long focal lengths when I'm out wandering around. I just don't "see" that way.

I know I'm well "behind the curve" on this stuff. So I'll close by saying the obvious - cell phone cameras aren't nearly as bad as I feared.

Here is a short list of soft focus lenses that I recently compiled. I posted parts of this in several previous articles. Of course there are many additional options, as can be seen on Jim Galli's old Tonopah site. So do not take this as a definitive list, OK?

The first section came from browsing the Clarence White edited journal "Pictorial Photography in America" from 1920 thru 1922. These journals reveal an interesting list of lenses -

120 Medium Format Optics

35mm format glass optics

35mm format plastic lenses

Years ago I shot large format film (4x5inch up to 12x20inch) and I followed Jim Galli's soft focus lens journey. The way he talked about his deep lens mine still cracks me up. His images from various soft focus lenses piqued my interest and his work became something of an inspiration for me in my own on-again/off-again soft focus lens explorations.

Jim had a wonderfully quirky website which dropped offline for me here in Europe. Perhaps it's still reachable from the US? Additionally, I see Jim is no longer part of the Large Format Forum. I'm not sure what happened. He'd been on that site for years.

A quick search reminded me that the Way Back Machine archives websites. Sure enough, they've archived a copy of Jim Galli's site from late 2019. I'm thrilled. Now I can go back and look at his work for ideas and understanding of how classic soft focus lenses can function.

Up to this point in my Soft Focus Adventures I have looked at filtration, optically induced softness, and nose oil finger "gunking" a lens or filter. What I would like to do now is to compare these three approaches side by side by choosing images that I feel best represent the soft focus effect.

Following with a previous format, I would like to first review available optics as I currently understand the market. Specifically I would like to present a list of 35mm SLR small format soft focus lenses.

35mm format glass optics

35mm format plastic lenses

In general I feel the lenses in the above list can be good for re-creating Pictorialist Era images. The following comparison attempts to share what I mean by this. I've taken the "best" looking images from four different soft focus approaches and put them side by side for easier review.

If you fancy trying your hand at old Pictorialist era images, something from the above list might appeal to you. And if your experience is anything like mine, it might take a bit of time, patience, and practice to get results that truly please. Patience seems to be the key in learning the capabilities and limitations of the soft focus practice.

Of the images in the above comparison I find I really like the meniscus lens. I literally stumbled on a configuration that works and see it at "f/2.8" to be pretty nice. Even at "f/4", this little cheap throw-away lens has some interesting properties to explore. A downside is it's a little funky to work with as two slim extension tubes are involved in getting the focus range approximately usable.

Just behind the meniscus lens "look", I like the Orton Effect digital softening filter. This tool is very configurable, and therefore very controllable. You can set the overlaying Gaussian blur, blend mode, and opacities to just about anything and watch what happens to an image. In the above example I chose a blend, opacity, blur width that, to my eyes, came somewhat close to duplicating the effects I get from the meniscus lens.

For pure hard-core optical effects, the Pentax 85mm f/2.2 Soft set at f/5.6 is pretty interesting. I'm not sure if/when/how I will ever come to real terms with the objective. When I go into the field it feels like a risk to take this lens and be somehow disappointed by the results and to come back with nothing. So I tend not to work too much with it. Maybe I should take my own advice and just dive in?

Should you seek some inspiration, check out Eric Lindbloom's "Angels at the Arno." It is a beautiful book filled with images made using a simple plastic lens (an old Russian Diana, I believe), which might prove the point that wonderful images can be made with just about anything.

Personally, I'm inspired by the "New Pictorialist" editor Chetworth delGato's Minolta 85mm f/2.8 Varisoft images. It's too bad those lenses currently cost the moon. There are many claims these lenses are rare, but I easily see them all over eBay. For a price, of course.

Turning to the David Hamilton/Max Stolzenberg stye images, here is a re-post comparison of soft filters vs nose oil (and Arnica Oil - ick! ack!!).

It goes without saying that the Nikkor Soft filters have little to no correspondence with Hamilton's nor Stolzenberg's "look." Similarly, the Arnica Oil is just too much. This is what I found when trying to work with Vaseline, too. No matter how lightly and thinly I tried to work with Vaseline or Arnica Oil, the whole plot was always, always, always over-softened and did little more than create a mess.

As with Goldilocks and the Three Bears there seems to be a happy medium. For me, that is the use of nose oil on a lens or, preferably, a UV Haze filter (to keep the gunk off your pristine glass). Just take a finger and gently rub the side of your nose and then smear it over the filter (or lens, if you really insist). It's quick, easy, and looks to mimic rather well the David Hamilton, Max Stolzenberg style. If you want to soften just the sky/trees, simply touch that part of the filter (or lens, again, if you really insist) that collects light from that part of the scene. If you don't "get" what I'm saying, one or two practice dabs with an oiled finger will get you pointed in the right direction.

Now, is this the actual technique that David Hamilton and Max Stolzenberg used and use? I have no way of knowing. But if it's their effect you're looking for, here is one way of "getting there from here."

As a demonstration of the possibilities of the greasy finger approach, consider an image I accidentally made during the 2016 traversee de Paris summer event for automobiles. Look at what is going on with the hood area of the Talbot-Lago sportscar. The Sony 16mm f/2.8 SEL I was using got "dabbed" by my greasy finger shortly after I arrived at la place de la Concorde in Paris.

I didn't catch the mistake until I was back home and looking at the mysteriously soft images I'd captured. Inspecting the lens quickly explained what had happened. To salvage something of the images I took that day with the greased up lens I cranked up the contrast. The out of the camera RAW are much much softer than this. Taking that into consideration, have a look at the following image and see how the hood "glows."

In prior articles I talked a little about a couple of lenses that might be useful in making soft images. I've also covered the effects of Nikkor Soft #1, #2 analog and Orton Effect digital filters.

Optical effects the Pentax 85mm f/2.2 and DIY meniscus optics seem to align somewhat closely with lenses of the Pictorialist era. The Nikkor Soft and to some degree the Orton Effect filters to my eye quickly recreate certain soft imaging styles from the 1970's and 1980's. These filters and lenses seem to have little relation, however, to what the much more current photographers David Hamilton and Max Stolzenberg did and do to create their soft images.

David Hamilton said something very similar to what is currently found on Max Stolzenberg's website.

Even from a casual glance it is clear the image has been modified to give softness in the image Max is talking about.

When I look at a partial list of gear that David Hamilton used, I don't see a single soft focus lens. Additionally, camera bodies generally don't give the kind of softness we are considering.

It's something of a mystery, then.

When I was younger I avidly followed David Hamilton's work. He was written up in the photography journals of the day, and one of the recurring topics was just how did Hamilton get those effects?

As I wrote earlier, I feel the first broad approach to generating the sense of softness is to shoot into the light. This was a classic way of wrapping a subject in a soft glow. I think this, coupled with three other things, is where David Hamilton started.

One of the three things he did was to push Ektachrome film which modified the color response of the film and increased contrast. The second was to take advantage of internal reflections off the lenses (sometimes called flare) which cut the contrast range. This may have conveniently offset the increased contrast introduced by the way the film was developed. The third thing that I feel came into play in Hamilton's images were the print technologies of the day.

If you compare the printing of his books against his last advertising campaigns perhaps you will see how his published work transitioned from a warm-tone grainy "look" to a crisper, more neutral tone, "cleaner" style as the technologies he used evolved over the years. I feel some of the original "charm" was for this reason missing from his last works.

Smaller format film naturally came with a certain level of grain. It was the clumping of silver halide crystals that produced grain. I contend that one of the effects of grain is to gently distance a viewer from the image. It takes a step from "reality" toward "non-reality." Book and magazine published images 40 years ago added a texture that increased the sense of removal from "reality", too.

It was a lesson I learned very early on. I had the opportunity to look at two original Edward Weston prints. One was of his famous nautilus shells, and the other was the even more famous peppers.

What I was looking at bore little resemblance to what I'd seen in publications. The originals were crisp and clear and had very subtle gray tones and not very deep blacks. It was like looking at the real things. They "felt" very differently to the images that had been mass reproduced. Publication technologies had subtly changed my viewing experience.

Shortly afterward I became a black and white print technician at Samy's Cameras photolab on Sunset Blvd. I learned that Grain was Good in a final print, just as long as it was sharp from edge to edge. Prints from 35mm and 120 format negatives all took on a certain "distance" between the viewer and the subject due to their obvious grain.

This is why I feel that between the film grain and print technologies that Dave Hamilton's work from the 1970's and 1980's have the "look" and "feel" that they do.

The second broad approach that David Hamilton took, and one that Max Stolzenberg takes is to deliberately soften an image. This is where the claim of not using soft focus filters becomes something of a curiosity.

Clearly, sections or portions of David's work take on a "glow" that can only come from _something_. Max's work seems to have adopted this "glowing" _something_ across a much broader range of work.

Yet, if I take a face value Hamilton's and Stolzenberg's claims that they only had a lens, a camera, film, talent, and did _not_ use any filtration, then how did they get the effects they did and do?

Friends and I used to speculate at great length on the topic. One friend felt David used Vaseline on his lenses. So we tried it and what a mess! That couldn't be it. Another friend heard that he left his lenses uncapped and let dust and dirt accumulate on them over the years. But that couldn't be it, either, as parts of David's work could be sharp while skies and trees in certain images were softened. Dirt and grime would lay themselves evenly across a lens surface, wouldn't it?

And so the debate went. We never were able to come up with a satisfactory explanation.

I thought about all of these things when I came up with the following Late Pandemic Oh I'm So Terribly Bored comparison. I re-shot a scene using, again, the Nikon Nikkor Soft filters. Then I shot the scene with an Arnica Oiled-up UV filter. After cleaning the UV Filter I took my forefinger and transferred a bit of along the side of the nose grease to the filter. Here are the results.

This time using a Nikon Nikkor-O 35mm f/2 pre-Ai single coated lens and shooting it wide open, I see that without any filtration or other image modifications that the subject is very sharp and that the background dissolves into a glorious softness. This, I feel, is a good demonstration of what David Hamilton did by shooting into the light, coupled with the lenses of his time. Yes, I know he used different subject matter, but you get the point. I hope.

The Nikkor Soft filters lower contrast and softens the entire scene. I don't find any resemblance between these filtered images and what David and Max create.

Looking at the Arnica Oiled-up UV filter I see exactly the kind of mess that I got 40 years ago with Vaseline. Even when applied very very thinly, Vaseline and Arnica Oil produce nothing but a mess. The image is messy. The filter is messy. I doubt very much that this is what David and Max use. Who would want to contend with such a mess?

Lastly, looking at the UV filter dabbed and streaked with side of the nose grease I feel we're finally getting somewhere. Compare my image with the two photographers images and I think you'll see what I'm pointing to.

A long time ago I learned that human nose greases were the finest oils found in nature. They are thin and for photographic purposes easy to control. Nose oils don't have the messy problem that Vaseline and Arnica Oil do, and nose oil is fairly easy to clean off a lens or filter with a bit of eye glass cleaner.

You can apply nose grease where you want, quickly, accurately, and you have a nearly unlimited, and perhaps the best part is it is entirely free zero cost supply of the stuff. And what noise grease does to subject shot into the light with a wide aperture lens is something quite magical.

Could it be that the "talent" of Max Stolzenberg and David Hamilton is in the carefully strategic placement of a nose oiled finger on the lens?

I'll leave you with this. Not wanting to mess a perfectly decent optic, I nose oiled a UV Filter. Take a look at the following and let me know what you think.