In prior articles I talked a little about a couple of lenses that might be useful in making soft images. I've also covered the effects of Nikkor Soft #1, #2 analog and Orton Effect digital filters.

Optical effects the Pentax 85mm f/2.2 and DIY meniscus optics seem to align somewhat closely with lenses of the Pictorialist era. The Nikkor Soft and to some degree the Orton Effect filters to my eye quickly recreate certain soft imaging styles from the 1970's and 1980's. These filters and lenses seem to have little relation, however, to what the much more current photographers David Hamilton and Max Stolzenberg did and do to create their soft images.

David Hamilton said something very similar to what is currently found on Max Stolzenberg's website.

Even from a casual glance it is clear the image has been modified to give softness in the image Max is talking about.

When I look at a partial list of gear that David Hamilton used, I don't see a single soft focus lens. Additionally, camera bodies generally don't give the kind of softness we are considering.

- Minolta SRT-101

- Minolta SRT-303

- Rokkor 28mm f/2.0

- Rokkor 35mm f/1.8

- Rokkor 55mm f/1.7

- Rokkor 58mm f/1.4

- Rokkor 58mm f/1.2

- Rokkor 135mm f/2.8

- Rokkor 80-200 f/4.5

- Polaroid SX70

It's something of a mystery, then.

When I was younger I avidly followed David Hamilton's work. He was written up in the photography journals of the day, and one of the recurring topics was just how did Hamilton get those effects?

As I wrote earlier, I feel the first broad approach to generating the sense of softness is to shoot into the light. This was a classic way of wrapping a subject in a soft glow. I think this, coupled with three other things, is where David Hamilton started.

One of the three things he did was to push Ektachrome film which modified the color response of the film and increased contrast. The second was to take advantage of internal reflections off the lenses (sometimes called flare) which cut the contrast range. This may have conveniently offset the increased contrast introduced by the way the film was developed. The third thing that I feel came into play in Hamilton's images were the print technologies of the day.

If you compare the printing of his books against his last advertising campaigns perhaps you will see how his published work transitioned from a warm-tone grainy "look" to a crisper, more neutral tone, "cleaner" style as the technologies he used evolved over the years. I feel some of the original "charm" was for this reason missing from his last works.

Smaller format film naturally came with a certain level of grain. It was the clumping of silver halide crystals that produced grain. I contend that one of the effects of grain is to gently distance a viewer from the image. It takes a step from "reality" toward "non-reality." Book and magazine published images 40 years ago added a texture that increased the sense of removal from "reality", too.

It was a lesson I learned very early on. I had the opportunity to look at two original Edward Weston prints. One was of his famous nautilus shells, and the other was the even more famous peppers.

What I was looking at bore little resemblance to what I'd seen in publications. The originals were crisp and clear and had very subtle gray tones and not very deep blacks. It was like looking at the real things. They "felt" very differently to the images that had been mass reproduced. Publication technologies had subtly changed my viewing experience.

Shortly afterward I became a black and white print technician at Samy's Cameras photolab on Sunset Blvd. I learned that Grain was Good in a final print, just as long as it was sharp from edge to edge. Prints from 35mm and 120 format negatives all took on a certain "distance" between the viewer and the subject due to their obvious grain.

This is why I feel that between the film grain and print technologies that Dave Hamilton's work from the 1970's and 1980's have the "look" and "feel" that they do.

The second broad approach that David Hamilton took, and one that Max Stolzenberg takes is to deliberately soften an image. This is where the claim of not using soft focus filters becomes something of a curiosity.

Clearly, sections or portions of David's work take on a "glow" that can only come from _something_. Max's work seems to have adopted this "glowing" _something_ across a much broader range of work.

Yet, if I take a face value Hamilton's and Stolzenberg's claims that they only had a lens, a camera, film, talent, and did _not_ use any filtration, then how did they get the effects they did and do?

Friends and I used to speculate at great length on the topic. One friend felt David used Vaseline on his lenses. So we tried it and what a mess! That couldn't be it. Another friend heard that he left his lenses uncapped and let dust and dirt accumulate on them over the years. But that couldn't be it, either, as parts of David's work could be sharp while skies and trees in certain images were softened. Dirt and grime would lay themselves evenly across a lens surface, wouldn't it?

And so the debate went. We never were able to come up with a satisfactory explanation.

I thought about all of these things when I came up with the following Late Pandemic Oh I'm So Terribly Bored comparison. I re-shot a scene using, again, the Nikon Nikkor Soft filters. Then I shot the scene with an Arnica Oiled-up UV filter. After cleaning the UV Filter I took my forefinger and transferred a bit of along the side of the nose grease to the filter. Here are the results.

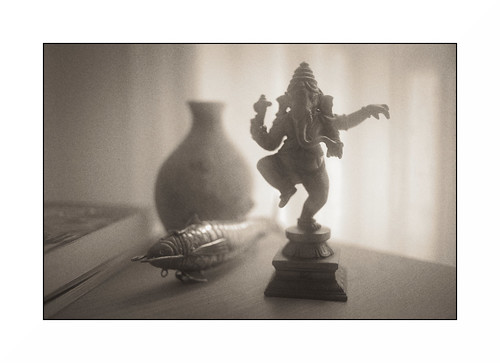

This time using a Nikon Nikkor-O 35mm f/2 pre-Ai single coated lens and shooting it wide open, I see that without any filtration or other image modifications that the subject is very sharp and that the background dissolves into a glorious softness. This, I feel, is a good demonstration of what David Hamilton did by shooting into the light, coupled with the lenses of his time. Yes, I know he used different subject matter, but you get the point. I hope.

The Nikkor Soft filters lower contrast and softens the entire scene. I don't find any resemblance between these filtered images and what David and Max create.

Looking at the Arnica Oiled-up UV filter I see exactly the kind of mess that I got 40 years ago with Vaseline. Even when applied very very thinly, Vaseline and Arnica Oil produce nothing but a mess. The image is messy. The filter is messy. I doubt very much that this is what David and Max use. Who would want to contend with such a mess?

Lastly, looking at the UV filter dabbed and streaked with side of the nose grease I feel we're finally getting somewhere. Compare my image with the two photographers images and I think you'll see what I'm pointing to.

A long time ago I learned that human nose greases were the finest oils found in nature. They are thin and for photographic purposes easy to control. Nose oils don't have the messy problem that Vaseline and Arnica Oil do, and nose oil is fairly easy to clean off a lens or filter with a bit of eye glass cleaner.

You can apply nose grease where you want, quickly, accurately, and you have a nearly unlimited, and perhaps the best part is it is entirely free zero cost supply of the stuff. And what noise grease does to subject shot into the light with a wide aperture lens is something quite magical.

Could it be that the "talent" of Max Stolzenberg and David Hamilton is in the carefully strategic placement of a nose oiled finger on the lens?

I'll leave you with this. Not wanting to mess a perfectly decent optic, I nose oiled a UV Filter. Take a look at the following and let me know what you think.

2 comments:

In the words of the great Jimmy Durante... "The nose knows" !

"...All of us have schnozzles... if not in our faces, then in our character, minds or habits. When we admit our schnozzles, instead of defending them, we begin to laugh, and the world laughs with us..." - Jimmy Durante

:-)

Post a Comment