In a prior article I took a look at copying 4x5inch black and white negatives using a 24megapixel full-frame digital camera and an old film-era macro lens.

It left me to ponder the question of how much more "resolution" could be gotten by moving the lens closer to a negative and stitching several image sections together. It could be interesting to find the point where the digital system would start recording film grain and give no further "resolution" increase by moving even closer.

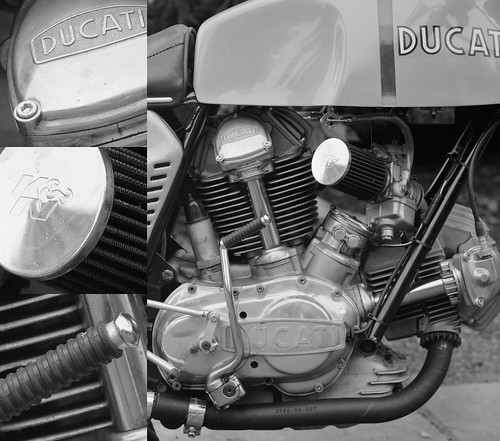

The subject is a lovely 1975 Ducati 750GT. I bought this from a friend who had made it into a quasi-"750 Sport." It was a gorgeous bike and I loved riding that Duc. One year I rode it to the Steamboat Springs motorcycle racing event from Oregon. She delivered 55miles per gallon a 75 miles per hour. Talk about efficiency!

This version of the 750cc 90 degree V-twin came with spring actuated valves, not the more legendary desomodromic valve train that Ducati is rightfully famous for. Still, the motor was sufficiently powerful, easy to control, and had nothing to rate against it as far as I was concerned.

Fabio Taglioni had designed or specified nearly everything about these bevel-drive bikes. The layout, engineering, and manufacturing were outstanding. My bike worked like a beautifully made watch. There was a finesse that seemed missing from all other motorcycles i ever rode (and I've ridden just about every road bike ever made from 1973 through to the late-1980's).

I owned another interesting spring valve Ducati. It was a 1977 860GT. Few people liked the bike and I can remember seeing new, unsold examples sitting of showroom floors well into the 1980's.

Never sure why people didn't like it, I found it had "grunt" on the road. It felt like a person could pull tree stumps out of the ground with one. I rode mine for years without experiencing any problems. It, too, had a finesse that was undeniable.

Even if I find such details interesting, these have nothing to do with photography. So back to is, shall we?

The following image is a single photograph taken of the entire negative using an early model Sony A7 24mpixel camera and an ancient Nikon Micro-Nikkor 55mm f/3.5 lens.

[As always, click on the images and then enlarge them to 100percent]

Entire negative in one shot -

Scene on the right

100percent enlarged sections on the left

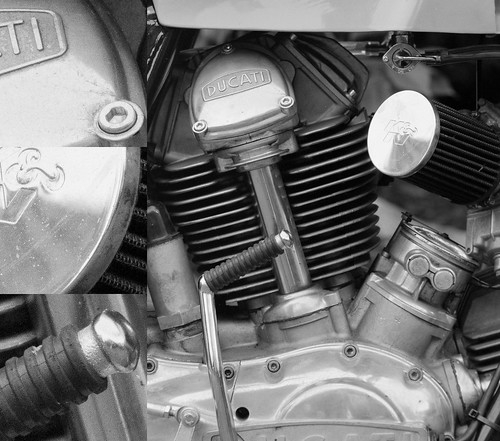

The following image is a single photograph that represents approximately 50 percent of the area of the entire negative.

50percent negative -

Scene on the right

100percent enlarged sections on the left

Lastly, the following image is a single photograph that represents approximately 25 percent of the are of the entire negative.

25percent negative -

Scene on the right

100percent enlarged sections on the left

As you can see, film grain is just becoming visible in the 50 percent enlargement. A stitched image of this magnification would be approximately 10,000 pixels across on the long dimension from a 4x5inch negative. Image details look pretty good to my eyes.

From the last image we can see that film grain is clearly visible in the 25 percent area enlargement. I'm not sure how useful it would be to make an image 15,000 or 20,000 pixels across on the long dimension with this grain size, but, as you can see, such a thing would be easily possible.

If I were to make prints larger than 20x24inches, perhaps I would "feel better" about photographing a negative in sections, and then stitching them into a rather large file.

I'm not sure how this would look in practice as I no longer have a printer and no place to store prints. On the other hand, for sharing some of my old work, I think a single full negative digital image should work just fine.

No comments:

Post a Comment